I’m closer to 50 than I’d like to admit, but there are things about my youth that I don’t think I’ll forget any time soon. Chief among them are the cars. I’ll spare you the entire list, as my father’s soft spot for “hard luck” cars resulted in a family car pedigree that might sound too much like the “begats”… If all of the cars my dad owned in my early years merged into a single automotive identity, its defining characteristics would be ample rust perforation, excess room for unbelted children to cage-match in during road trips, at-best 8-Track playback capability, and an overall aesthetic most young males would might call “birth control.” I certainly didn’t help the situation as I played unintentional bumper cars 3 times in 6 weeks in the 1978 Ford Fairmont station wagon, ultimately driving its value from somewhere around $12 down to about the current price of Enron stock. My dad was forgiving and teed up an 1832 Datsun B210 with flat black house paint for my driving needs. It was not, shall we say, a car that helped my social prospects. With occasional exceptions, all of these cars did the thing they were supposed to do—get us from A to B.

When it was time to buy my lieutenant-mobile, I set about to change my family’s tree in the automotive department with a sweet, midnight blue Acura Integra. While I still turn my head every time I see one on the road 24 years later, that car came with just as many painful memories… on the first of every month due to compounding 6.9% APR. I didn’t know it at the time, because all of my math capacity went into managing the 60:1 rule for check rides, but that car was not just draining my meager bank account it was literally making me poorer every year due to its most stealthily hidden feature: depreciation.

I graduated college with a small amount of credit card debt, but my $22,000 car loan on a car that became worth 20% less every year was dragging my net worth down faster than a Viper guns a… (I’ll let you finish this part…). The truth is most cars, with the confounding exception of Jeep Wranglers in my zip code, depreciate about 20% per year for the first five years. These days, it’s hard to get a decent brand-new car for a lot less that $30K and incredibly easy to rationalize into a $50K+ set of wheels.

As a tribe that’s got a well-developed crosscheck, we’re used to scanning airspeed, altitude, AMRAAMs and other indicators of well-being. When looking at our balance sheet, two of the most important instruments are the net worth gauge and the savings rate indicator. New cars cause problems for both.

Cars and Net Worth

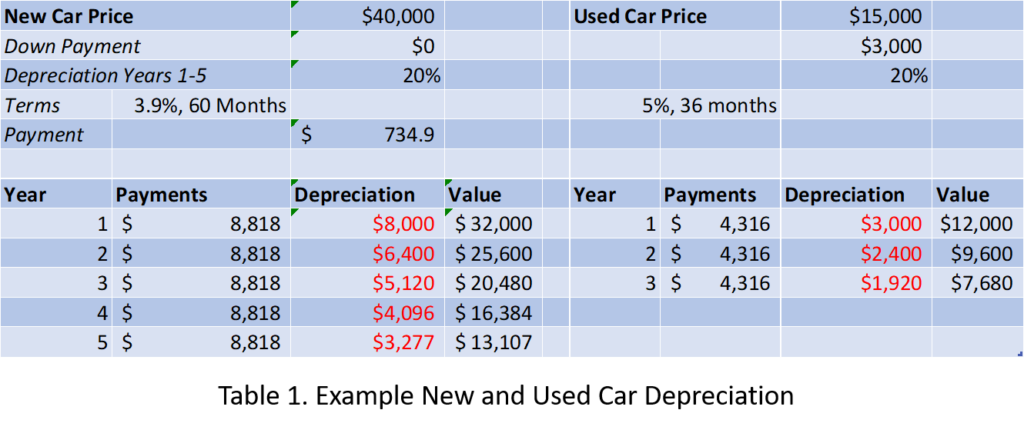

Table 1 is a simple comparison of the math behind buying a new car for $40K and a decent used car for $15K. Key assumptions include, a lower interest rate for the new car and a non-zero down payment for the used car.

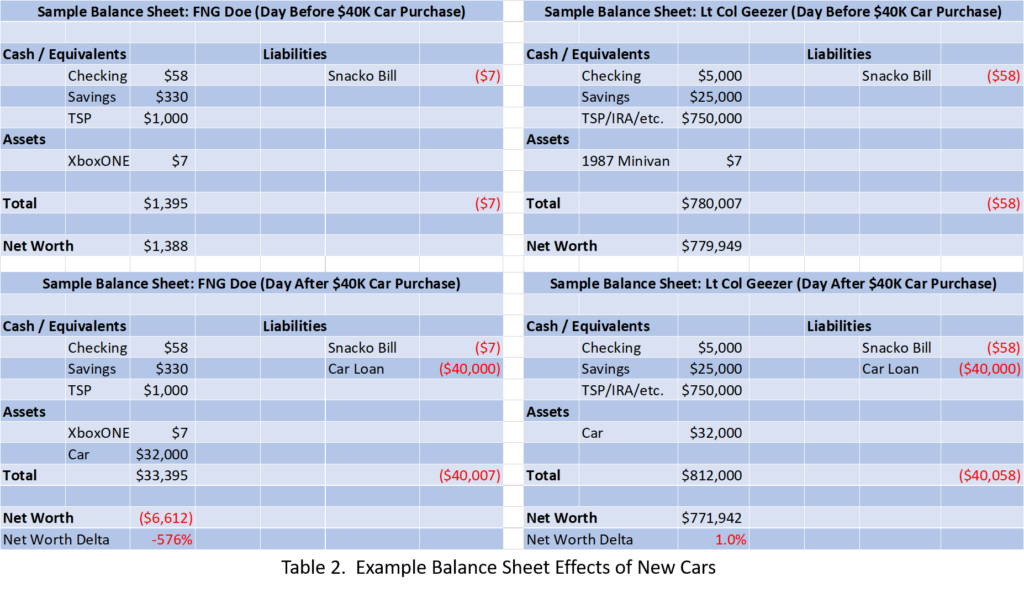

Most of us enter the service with a net worth (assets minus liabilities) around $0. That’s okay. Real life monopoly doesn’t fill up your bank account before the first dice roll. But let’s examine the balance sheet effect of the new car from Table 1 on two different officers in Table 2. FNG Doe is pretty stoked to driving his sweet new ride, but his net worth plumets by 576% the day he buys it. Lt Col Geezer is pretty happy to put the 1987 minivan in the rearview mirror too, but the effect on his net worth is only 1.0%!! Both officers can get from point A to point B, but one is moving in the wrong direction to get to his/her financial future.

Cars and Savings Rate

The other dial—savings rate, matters too. You’ve likely heard rules of thumb about saving 10%-20% of your income in order to fund retirement. Many of us struggle with the “gross vs. net” question, but I’d argue that if you’re hitting 15% of either, you’re crushing most Americans. Car payments can be the biggest monthly budget item after a mortgage payment, but with few exceptions, we have a lot of control over what we spend on things that, at their core, go from A to B. I don’t think it’s a revelation to say that the more we spend on car payments, the less we’ll have to save and invest. Rather, I’ll offer a few TTPs for funding cars in order to free up more cash for retirement savings:

- Drive them longer. It used to be that only Craigslist had vehicles with 200K+ miles. With more reliable models, it’s not uncommon to find them on used car lots too. Driving a car longer before replacing it gives you a lot of years where the required car payment is $0. Switching cars adds transaction costs (taxes, etc.) and another depreciating asset to your world. (I’m pretty sure this is how my dad accumulated so many birth control cars.)

- Save for cars in a sinking fund rather than financing them. When a $500/month payment can go to your bank account instead of your bank, you can build car savings at a $6K/yr clip. If you pay off a car in 5 years, but drive it for 10, you’ll have at least $30K available for the next purchase.

- CAUTION: An advanced, but riskier version of this maneuver is to save inside a taxable brokerage account with equities. The potential for returns is higher, but the potential for loss of principle is too. That said, over 80% of rolling 5-year periods in the U.S. market are at least level… Additionally, if you do realize gains from this strategy, you’ll pay capital gains tax when you sell the assets to purchase the car.

- Pay Cash. When financing a car, it’s incredibly easy to let squishy-math drive you into spending more than you planned. “What’s $31 more a month?” “Who wouldn’t buy an extended warranty?” When you pay cash, there’s a built-in limit to what you can pay. It also cuts down on time spent in the financing office of the dealership.

- Never lease. Leasing is hands-down the most expensive way to operate a car. If you’re not in your decumulating stage, legitimately worried about estate taxes, leasing probably isn’t compatible with building wealth.

- Buy Used. The Millionaire Next Door laid out the truth that most first-generation millionaires purchase and drive late-model used cars. For the core purpose- they’re generally pretty reliable and safe. This both dodges the worst of depreciation and creates an option to reduce payments.

- Avoid luxury brands. Expensive things have expensive things. Routine maintenance and parts cost more on luxury brands which directly limits cash for other priorities. They also frequently depreciate faster.

When Can I Buy an Expensive New Car?

This article isn’t meant to be a wet blanket on your automotive self-image forever. But the name of the game is putting dollars away to grow net worth, not giving dollars away to shrink net worth. Early in your career, you can get some serious mach on your investment compounding, but you won’t have that option if your dollars are depreciating away in a car. Later in your career, you’re likely to have two things working for you:

- The amount you lose to depreciation on a newer car will be budget dust compared to your net worth.

- Your payment (should you choose to have one) will be a tinier fraction of your monthly cash flow.

That crossover point, when car expenses just aren’t a major part of your financial picture, will be different for all of us. To build wealth, it’s critical to wait for it. To enjoy your wealth, it might be good to celebrate it. Fights on!

Winged Wealth Management and Financial Planning LLC (WWMFP) is a registered investment advisor offering advisory services in the State of Florida and in other jurisdictions where exempted. Registration does not imply a certain level of skill or training.

This communication is for informational purposes only and is not intended as tax, accounting or legal advice, as an offer or solicitation of an offer to buy or sell, or as an endorsement of any company, security, fund, or other securities or non-securities offering. This communication should not be relied upon as the sole factor in an investment making decision.

Past performance is no indication of future results. Investment in securities involves significant risk and has the potential for partial or complete loss of funds invested. It should not be assumed that any recommendations made will be profitable or equal the performance noted in this publication.

The information herein is provided “AS IS” and without warranties of any kind either express or implied. To the fullest extent permissible pursuant to applicable laws, Winged Wealth Management and Financial Planning (referred to as “WWMFP”) disclaims all warranties, express or implied, including, but not limited to, implied warranties of merchantability, non-infringement, and suitability for a particular purpose.

All opinions and estimates constitute WWMFP’s judgement as of the date of this communication and are subject to change without notice. WWMFP does not warrant that the information will be free from error. The information should not be relied upon for purposes of transacting securities or other investments. Your use of the information is at your sole risk. Under no circumstances shall WWMFP be liable for any direct, indirect, special or consequential damages that result from the use of, or the inability to use, the information provided herein, even if WWMFP or a WWMFP authorized representative has been advised of the possibility of such damages. Information contained herein should not be considered a solicitation to buy, an offer to sell, or a recommendation of any security in any jurisdiction where such offer, solicitation, or recommendation would be unlawful or unauthorized.