How Fighter Pilots Think About Emergency Funds

The military and FAA both have rules, written in the blood of those whose misfortune generated the need for the rule, about keeping a fuel reserve. Those of us who’ve landed below the calculated emergency number know the sinking feeling… the overwhelming regret… the silent pleading with our higher power, “Please let me get on the ground and I will never push the gas numbers again…” Like most bad situations in an airplane—there are those that have, those that will, and those that will again.

Keeping an emergency fund is a lot like keeping emergency reserve gas in your airplane. Run out of gas? Probably going to crash. Run out of cash? Sure, it doesn’t sound ideal, but you don’t exactly fall out of the sky, right?

What is an Emergency Fund?

The blinding flash of the obvious is that an emergency fund is cash, sitting alert in a separate account, waiting for a mission you hope it never scrambles for. An emergency fund is not an investment—it’s insurance. While I’m fond of the silver-lined suggestion that crisis and opportunity are close cousins, I wouldn’t consider an emergency as chance to gain. Rather, most emergencies are a chance to mitigate loss.

Cash on hand insures against the severity of emergencies, much like gas on board insures against the severity running out of gas.

Given that an emergency fund is a self-funded insurance policy, not an investment, we should cage our expectations. Cash sitting in an emergency fund costs money (or at least opportunity) just like insurance costs money. Insurance policies are not investments (certainly not good ones anyway).

Emergency Cash—How Much Do You Need?

Before looking at the pros and cons of keeping emergency cash, let’s consider how much emergency fund is enough. You’ve likely heard the rule of thumb that three to six months of expenses is sufficient. But is this all spending for the month, or the bare bones?

A good technique is to start at bare bones. What bills are must-pay?

- Food (groceries, probably not dining out)

- Mortgage/Rent

- Utilities (water, electricity, gas, phone/internet)

- Transportation (car payment, gas, insurance, tolls)

- Clothing

Each family has to review their own cashflow to determine the needs, wants, and wishes breakdown. Periodically doing so is good financial hygiene anyway, and this article isn’t going to argue for a bloated emergency fund.

Emergencies come in all shapes and sizes, so it might be wise to consider some other categories too:

- Rental property expenses (vacancy, major appliance, insurance deductible, etc.)

- Small business expenses (payroll, operating funds, deductibles, etc.)

- Home / Car insurance deductible (e.g., hurricane deductibles are usually chunky 5-figure numbers)

- Health insurance catastrophic cap (usually four to five figures)

If your family is still on active duty, it’s reasonable to assume that your check will still show up even when Congress and the White House engage in the periodic jackassery of government shutdowns. However, we’ve been cursed to live in interesting times, so I’d argue there’s a non-zero chance of DFAS having to short you for a few paychecks while the gears of government grind.

If time on active duty is growing short, the predictability of a steady paycheck dries up too. Airlines furlough. Corporations layoff. Customers hoard their own cash in lean times. Life after active duty requires different emergency fund math.

The Case Against Emergency Funds

The prosecution’s arguments against keeping cash are compelling.

- Inflation: Cash sitting in an account, including the disingenuously-named “High-Yield Savings” accounts, is decaying at the rate of inflation. Historically, that’s an average of 3% per year, but like most financial averages, it’s rarely 3% in any year. I suspect few of us feel like it’s 3% here in 2021.

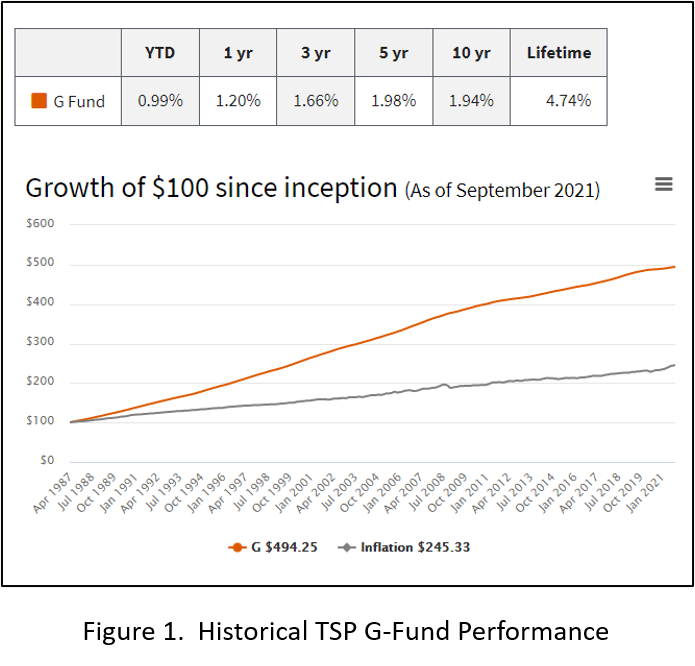

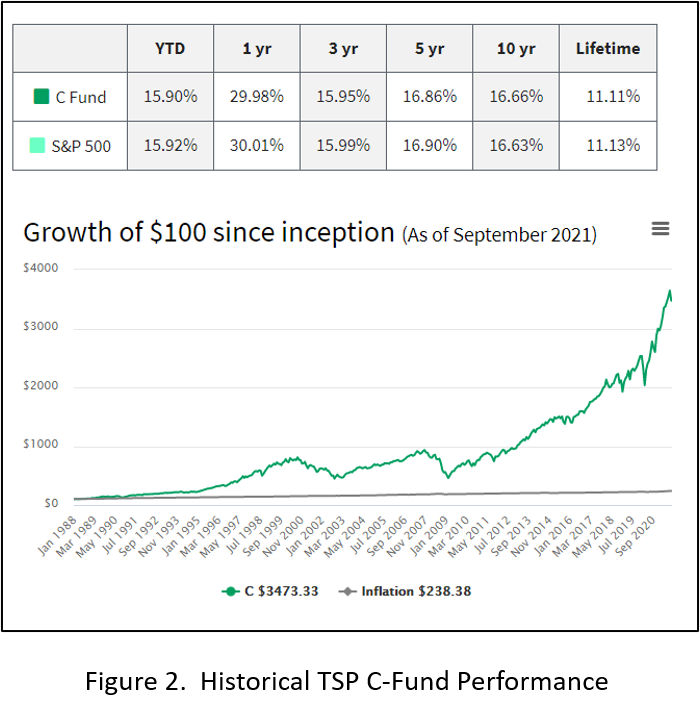

- Portfolio Drag: Any asset class that gets a lower return than the best performing asset class is pulling the return of the whole portfolio down. A quick look at Figure 1- the historical performance of the TSP G-Fund and Figure 2- the TSP C-Fund illustrates this idea. The C-Fund’s historically higher return would be diluted with any mixture of the G-Fund, right?

- Over the decades—yes.

- During a bear market—it depends. Cash and other non-correlated assets allow rebalancing.

Cash isn’t returning even what the G-Fund returns, and this article is about cash for emergencies, not investments. However, the point remains that cash prevents investment in more productive asset classes the same way that trash hanging on wings prevents efficient high-altitude flight.

- Tax Drag: Aunt IRS taxes interest earned on cash at your higher ordinary income rate, e.g., 22%+. She’s nicer to your capital gains from mutual funds and real estate, normally discounting the bill to 15% or less.

- Spending Drift: When there’s a General of Jack, how much do you pour? When there’s a trough-size bowl of M&Ms, how many do you eat? If you look at your accounts and see $50,033 sitting there, it’s awfully tempting to justify higher spending. At least it feels like putting cash to work when you upgrade to 90-inch TV…

- Alternatives: Credit cards, home equity loans/lines of credit, liquid investments (e.g., shares of stock or mutual funds) and even reverse mortgages can all provide sources of income. Yet, if the rainy day never shows up, these sources don’t induce portfolio drag, tax drag, or spending drift.

- Probability: If you’ve been able to cash flow your needs for a few decades, even the big ones like cars and roofs, you probably feel pretty good about the odds that you’ll encounter a cash need that you can’t power through.

The Case for Emergency Funds

It’s been said that a person with experience is not at the mercy of a person with an opinion. Those who lived through the Great Recession and its aftermath noticed a few things:

- Credit isn’t always available: In the Great Recession, banks unilaterally cancelled credit cards and HELOCs. Banks lowered borrowing limits.

- Emergencies aren’t always fast: The stock market took nearly 4 years to recover after the Great Recession. While that shouldn’t drive a 4-year cash load, it should calibrate our thinking about how credit availability isn’t a light switch. It may take time for conditions to reset and credit to flow the same way.

- Asset prices decline too: At the same time you need cash for an emergency, it’s not going to feel good to sell stocks or real estate at a loss. Your balance sheet takes a double whammy when you have to lock in losses and then immediately deploy the cash for a crisis purpose.

- Interest Drag: In the same way that low-return asset classes cause drag on portfolio return, paying interest on money borrowed for an emergency drags down overall return as well. While earning .05% interest in a “High Yield Savings” account isn’t exciting, paying9% interest on a credit card because of miscalculated emergency probability won’t be much fun either.

- Bargaining power: Prices tend to decline in recessions, but recessions aren’t the only causes of emergencies. The use of credit costs money to both buyers and sellers. Cash still causes emotional reactions. Unless you’re bargaining against a truly ice-veined opponent, waving some cash at the transaction has a high pK of lowering your cost.

- Sense of security: Some people are just going to feel better knowing they have cash. We don’t max-perform our money to win some math equation. We max-perform our money so we can feel happy, meet our needs, and feel secure in our future.

- Probability: Bloviators on cable “news” make a living successfully predicting thousands of the last zero actual calamities. But the Great Recession did in fact happen and most of us felt it. The Coronavirus Pandemic wasn’t on our radar in 2019, yet here we are, sorting through the aftermath nearly two years on. If we could predict them, they would be savings goals, not emergencies.

The Verdict

I’ll wager that this article won’t convince diehards on either side of the argument. If you didn’t come to your opinion by way of logical reasoning, you’re unlikely to change it for the same reason. Fortunately, an emergency fund isn’t a binary.

If keeping three to six months of cash is intolerable to your senses, perhaps whittle the number down a bit. Instead of cash for all expenses, perhaps just funding the most dire will suffice.

If you’re pro-emergency fund, but worry that maybe you are losing out by hoarding too many greenbacks, why not revisit your assumptions and apply a bit of Marie Kondo to the top-line number? If you worry about a market crash the next day after you deploy part of your emergency fund, perhaps dollar-cost average any excess.

Cleared to Rejoin

If you take one nugget away from this article, consider the concept: an emergency fund is insurance. If you don’t expect to earn money on your Term Life Policy, but you’re willing to pay for it anyway, then you’ve already admitted you’ll pay for insurance.

At the same time, we carry insurance to cover truly catastrophic events. If selling some shares of stock at a loss to free up cash isn’t actually a catastrophe to you, then there’s an argument that you’re already self-insured against anything up to the amount of your liquid assets anyway.

Perhaps the best thing you can do? Talk it over with your spouse and make sure you’re on the same flight plan. When Master Caution light flashes, you’ll want to resolve that emergency together!

Fight’s On!

Winged Wealth Management and Financial Planning LLC (WWMFP) is a registered investment advisor offering advisory services in the State of Florida and in other jurisdictions where exempted. Registration does not imply a certain level of skill or training.

This communication is for informational purposes only and is not intended as tax, accounting or legal advice, as an offer or solicitation of an offer to buy or sell, or as an endorsement of any company, security, fund, or other securities or non-securities offering. This communication should not be relied upon as the sole factor in an investment making decision.

Past performance is no indication of future results. Investment in securities involves significant risk and has the potential for partial or complete loss of funds invested. It should not be assumed that any recommendations made will be profitable or equal the performance noted in this publication.

The information herein is provided “AS IS” and without warranties of any kind either express or implied. To the fullest extent permissible pursuant to applicable laws, Winged Wealth Management and Financial Planning (referred to as “WWMFP”) disclaims all warranties, express or implied, including, but not limited to, implied warranties of merchantability, non-infringement, and suitability for a particular purpose.

All opinions and estimates constitute WWMFP’s judgement as of the date of this communication and are subject to change without notice. WWMFP does not warrant that the information will be free from error. The information should not be relied upon for purposes of transacting securities or other investments. Your use of the information is at your sole risk. Under no circumstances shall WWMFP be liable for any direct, indirect, special or consequential damages that result from the use of, or the inability to use, the information provided herein, even if WWMFP or a WWMFP authorized representative has been advised of the possibility of such damages. Information contained herein should not be considered a solicitation to buy, an offer to sell, or a recommendation of any security in any jurisdiction where such offer, solicitation, or recommendation would be unlawful or unauthorized.