The first time I remember seeing my dad’s W-2, he made about $30,000. Slightly less than 20 years later, my 2Lt pay was about the same figure. My family had modest means, but as a 2Lt I certainly couldn’t afford the standard of living my parents had achieved over decades of income. Inflation meant that my $30K didn’t stretch as far as my dad’s $30K did almost 20 years earlier. Our society is infatuated with the concept of a millionaire.[1] But does a million dollars really matter anymore?

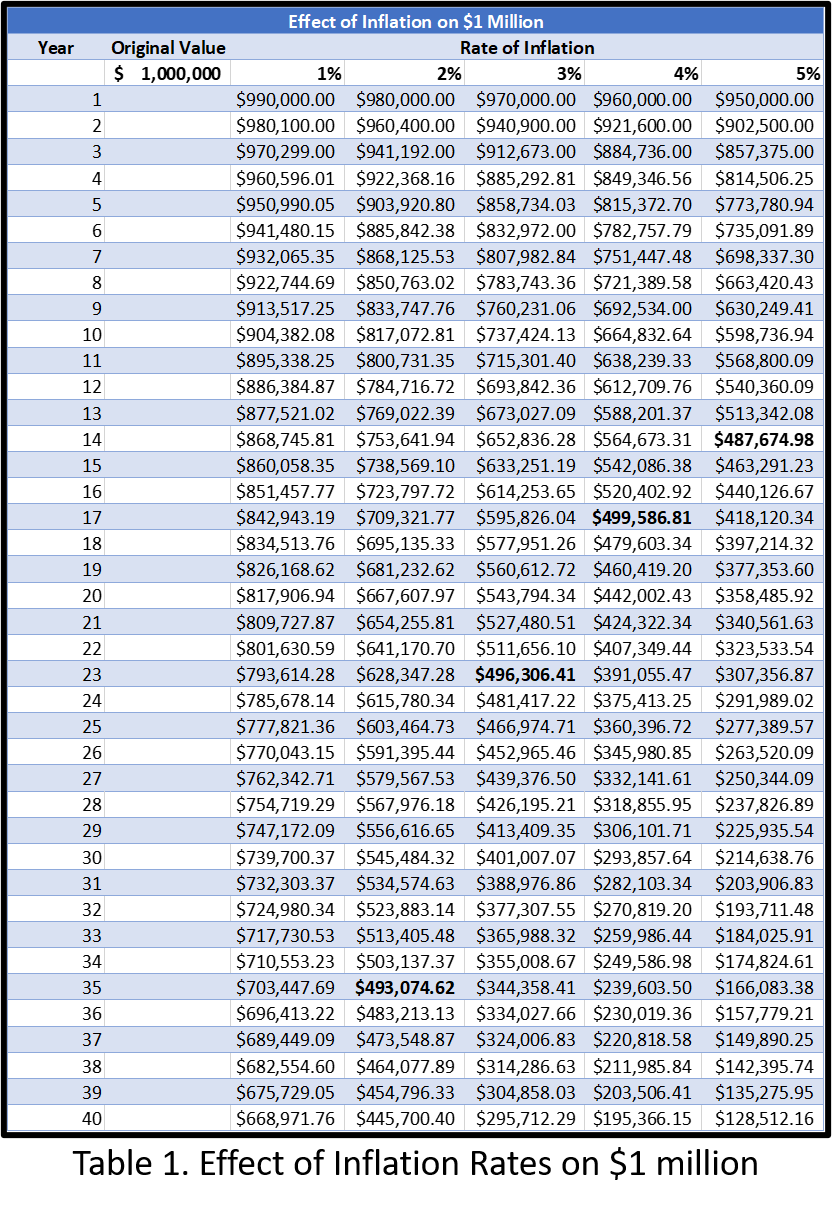

Inflation is the (usually) slow increase in prices over time. Certain things seem to defy inflation like Costco hot dogs (by company choice) and the price of a Coke in the squadron snack bar (because no one will pay more than $.50 or maybe snackos can’t do math?), but most prices increase over time. One dollar just won’t buy what it used to. Adding a few zeros after the dollar doesn’t affect inflation. Table 1 is a stark reminder what the power of inflation can do to seven figures.

A few take-aways from this table might be helpful. The “Rule of 72” is a common shortcut for determining how long an investment will take to double given a specific interest rate.

72 ÷ 2 (2% return) = 36 years for the investment to double.

The rule of 72 works the same for inflation, which is effectively a negative interest rate.

72 ÷ 2 (2% inflation) = 36 years for the investment to be cut in half by inflation.

The Federal Reserve’s inflation target is 2% for most non-food/energy goods. So, if things go “technically perfect” your $1M will be worth about half after 35 years. If you have $1M when you retire at 65, then your 100-year-old self will really feel inflation, but your 75-year-old self won’t get hit as hard.

If inflation kicks up to 5%, which is a good proxy for college and healthcare inflation, you can see that it only takes 14-15 years to lose half of your original purchasing power. Inflation sneaks up and steals your money from behind. It’s a key reason to be sensitive to the amount of cash you retain as part of your net worth and a reason to avoid sizable income tax refunds. Your favorite Uncle doesn’t pay interest when you overpay your taxes, and his friend inflation slices a few percent of the value off your dollars before returning them on April 15th.

So, Seriously Does it Matter?

In short—hell yes. My refrain usually sounds something like, “Invest wisely over the decades so you can have choices and wealth when you no longer want to work to provide for your needs and wants.” When you’re a lieutenant, saving 10% of income might result in putting away $5,000-$6,000 per year. In the Turning Lieutenants into Millionaires series, I explored how it is technically very simple for military officers to become millionaires comfortably earlier than most of us would like to permanently give up work. Our society idolizes millionaire status by incorrectly associating a million-dollar net worth with the ability to spend a million dollars in a given year. It doesn’t take a degree in rocket surgery to understand that those are two wildly different concepts. The literature on typical millionaire behavior (e.g., The Millionaire Next Door) makes it pretty clear that millionaires tend to accumulate that wealth by living frugally on modest income.

So why does a million-dollar net worth matter if it implies still relishing in the purchase of one of those Costco tube steaks or still getting a Coke in the snack bar for $.50? Because it’s still very rare air. The median net worth in America is about $104K and the median income is about $65K across all ages. So, to accumulate a million dollars of net worth means that you’ve outperformed the vast majority of Americans by a factor of 10. It’s like BFM’ing a 747 in a Viper! That accomplishment signifies discipline over time and appreciation of the power of compounding—skills that aren’t widespread in our society. What’s more, while $1 million might not be quite enough to retire on for most retired officers, the age at which you achieve your first $1 million can suggest what the score board will say when it counts as you enter your 60’s.

For easy math, let’s say you achieve a $1 million net worth at age 42 and can earn 7.2% after inflation. Then the rule of 72 says you’ll have $2 million at 52 and $4 million at 62. If your bar napkin retirement plan involves the 4% Safe Withdrawal Rate, then at 62, you’re looking at $160K of income in today’s dollars—not counting your military pension and potential early access to Social Security. That’s essentially the standard of living of a 20-year Lt Col with a little bonus action—not bad when you probably aren’t paying for a house or college, etc.!

The Barenaked Ladies may have set the gold standard for what one could do with $1 million, but you may have goals that go beyond a K-Car or exotic flightless birds. The real question is what are your goals? A $1 million net worth in your 40’s is mathematically great on a military salary, but probably isn’t going to support an early “FIRE” (financial independence, retire early) lifestyle unless you throttle way back on consumption. Likewise, if you spend all of your years diligently plugging away in accumulation mode, you need to plan for how to manage decumulation in your senior years.

[1] Although billionaires are certainly proliferating enough these days…

Let’s assume that you accumulate a $2 million net worth in your early forties, perhaps boosted by a working spouse and frugal lifestyle. The rule of 72 and a 7.2% rate of return suggests an $8M nest egg at age 62. But you’re 62, young by modern working standards and used to living on a fraction of what your assets would enable, so will you just start spending more because you can? It might be harder than you think. The 4% rule would have you withdrawing $320K per year starting at 62. What will you do with the extra money? Do you have plans to give charitably? How will you manage income, estate, and or inheritance taxes that could come from both an outsized income and net worth when you’ve lived frugally for your entire working life?

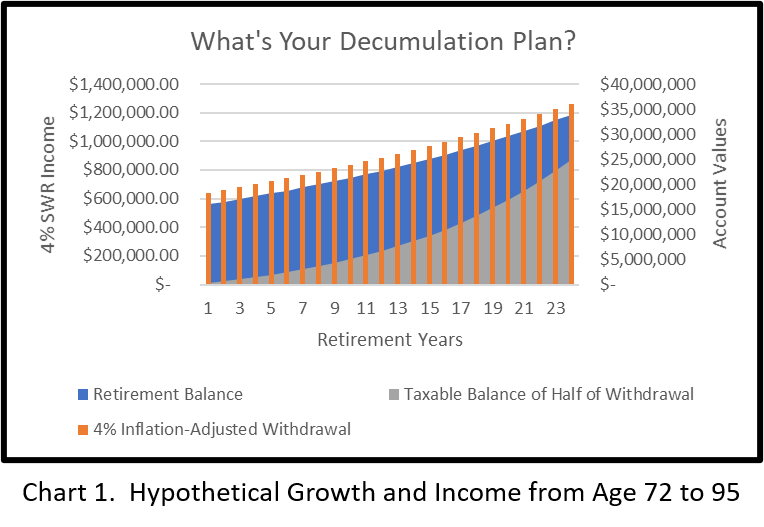

Chart 1 gives a slightly more extreme, but not implausible example. Continuing with the previous number, let’s say you keep working, accumulating, and living frugally until age 72. Now your nest egg is $16 million. For ease, let’s assume its somehow 100% in Roth IRA accounts, so you don’t have to worry about Required Minimum Distributions. Finally, let’s assume that since you probably won’t just start spending like a drunken congressman just because you hit age 72, so you’ll only spend half of your 4% withdrawal each year (adding 3% for inflation) while investing the remaining amount in a taxable account. If you keep your assets invested earning 7.2%, you can see that your retirement account eventually grows to comfortably over $30 million and the taxable account has over $20 million. While I don’t know what estate tax exemptions will be in the future, they’re currently at $11.7 million per person with a federal rate of 40% after that. I don’t have heartburn with your estate plan being “let Uncle Sam have his cut,” but 40% of a $50 million estate is $20M. I’ll go out on a limb and wager that most of us can think of some cause that could use the $20M more effectively.

Alright, back to reality. I’m not too worried about fighter pilots solving the problem of what to do with extra money, but I highlight the example to suggest that decumulating can be its own set of challenges after accumulating for a lifetime. The balance between accumulation and decumulation is the essence of financial planning over your lifetime and will reflect your general sense of financial peace of mind.

So does a million still matter? Absolutely. You’re goal-oriented—from meeting step time to leveling off at exactly FL 310 at .85M and shacking the push time. Setting and achieving a flight path to ensure that you pass $1 million on your way to your target is key to making sure you arrive at and hit the target. A million dollars probably isn’t a worthwhile annual cashflow goal on a military salary, but it is a great net worth milestone to achieve the freedom and decision space you’ll continually want more of as you age. Inflation will continue to erode the spending power of $1 million, but it’s probably going to be a while before the Barenaked Ladies reprise the tune as “If I had a Billion Dollars…” so we’ll all benefit from keeping a balance between accumulation mode and decumulation mode as we manage a lifetime of wealth. Fight’s on!

Winged Wealth Management and Financial Planning LLC (WWMFP) is a registered investment advisor offering advisory services in the State of Florida and in other jurisdictions where exempted. Registration does not imply a certain level of skill or training.

This communication is for informational purposes only and is not intended as tax, accounting or legal advice, as an offer or solicitation of an offer to buy or sell, or as an endorsement of any company, security, fund, or other securities or non-securities offering. This communication should not be relied upon as the sole factor in an investment making decision.

Past performance is no indication of future results. Investment in securities involves significant risk and has the potential for partial or complete loss of funds invested. It should not be assumed that any recommendations made will be profitable or equal the performance noted in this publication.

The information herein is provided “AS IS” and without warranties of any kind either express or implied. To the fullest extent permissible pursuant to applicable laws, Winged Wealth Management and Financial Planning (referred to as “WWMFP”) disclaims all warranties, express or implied, including, but not limited to, implied warranties of merchantability, non-infringement, and suitability for a particular purpose.

All opinions and estimates constitute WWMFP’s judgement as of the date of this communication and are subject to change without notice. WWMFP does not warrant that the information will be free from error. The information should not be relied upon for purposes of transacting securities or other investments. Your use of the information is at your sole risk. Under no circumstances shall WWMFP be liable for any direct, indirect, special or consequential damages that result from the use of, or the inability to use, the information provided herein, even if WWMFP or a WWMFP authorized representative has been advised of the possibility of such damages. Information contained herein should not be considered a solicitation to buy, an offer to sell, or a recommendation of any security in any jurisdiction where such offer, solicitation, or recommendation would be unlawful or unauthorized.